My second great-grandmother, Catharina Burk, stands out when I think about strong women in my line. In addition to weathering hardships during the early 1800s, she fought to right a wrong and positively change her community.

Catharina Burk Haag was born in 1817 in Arzheim, Germany, about 328 miles from Berlin, to Bernard Burk and Anne Barbara Glasgen. This small settlement has existed since 868 AD, although excavations show that it dates back to sometime in BC. Since 1970, it has been incorporated into the city of Koblenz. It is now referred to as Koblenz-Arzheim, which has 2200 residents.

In 1832, at 15, Catharina arrived in Baltimore from Germany with her father, mother, and several siblings. The family settled in Evansville, Indiana. She married George Haag and gave birth to their first child when she was 21. Like many wives in the 19th century, Catharina had a large family: 8 children, all boys except her firstborn. In 1859, just a year after her last child was born, and at the age of 42, her husband died, leaving her to not only take care of the six remaining children (two had already died) but also manage the family farm.

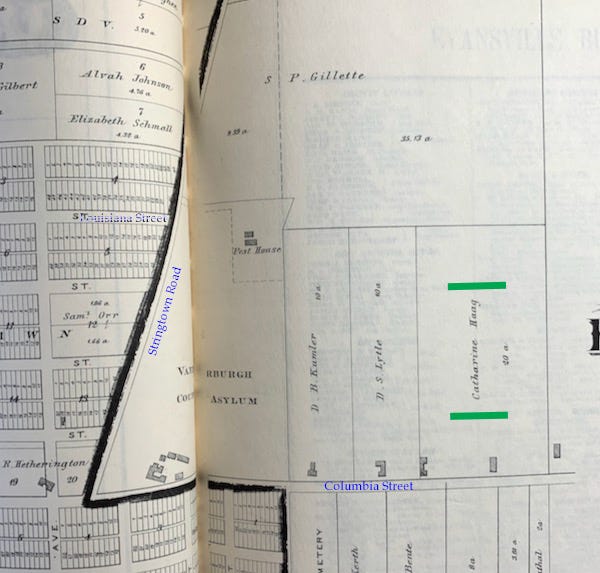

Catharina’s 20-acre farm was located in Evansville, approximately 330 feet from the Pest House, the county-run facility for indigent residents with infectious diseases. This 40-acre piece of land included the Vanderburgh County Asylum buildings and superintendent quarters built at the front edge of the property. Those buildings, also called the Vanderburgh County Poor Farm, were for the indigent and the "incurably insane." Behind that facility was an orchard, garden, and cemetery. The Pest House was isolated at the back end of the property to keep the illness from spreading through the larger facility.

Although smallpox was not quite at epidemic levels in May of 1875, The Evansville newspapers printed several stories about smallpox at the Pest House.

In May 1875, Catharina Burk Haag's son Carl, age 17, was plowing the field on their farm. Within a few days, he became sick and died of smallpox. While ill, he stayed at home with the other family members. After his death, the other children burned his clothing in the field. Ten days after Carl died, on June 2, 1875, his two older brothers, George, 25, and William, 21, died.

The local newspaper posted a story about the deaths of the two older children. “Physicians allege that the last two young men who died would not have been taken with the malarial disease if they had deserted the house till it was fumigated and buried the clothing of their deceased brother instead of burning it.”

Regardless, Catharina lost three sons in less than two weeks. In addition to her children's deaths, she lost their help on the farm. She had one remaining son, Henry, who was still at home. Her son John was married and lived on the property. My great-grandfather, Peter, also married and lived several miles away on his own farm. Even though Peter Haag didn’t live right there, I imagine that he also helped on her farm through this challenging time.

Mrs. Haag was not going to sit still and allow her children’s deaths to be ignored. She believed that the deaths of her children were due to negligence on the part of the county and city. Just seven days after George and William died, she filed suit against the Vanderburgh County Commissioners for their mishandling the treatment of the patients of the Pest House, causing her sons to catch the disease. She asked for $20,000 in damages, over a half million in today's dollars. In September of 1875, the case was brought before the Circuit Court. Unfortunately, the court believed there were insufficient grounds and dismissed the case.

Catharina refused to give up, appealing her case to the Indiana Supreme Court, where she explained she had spent $500 for "nursing, care, and medical attention" for her three children. Also, the court records charged that the Pest House "burned the clothing taken from the bodies of persons who had died from or had been treated for smallpox in the pest house out in the open air." The offensive fumes, smells, and smoke around Catharina's land rendered her home disagreeable, offensive, and dangerous. She prayed that the pest house would be declared a nuisance and removed.

In May 1878, the Supreme Court reversed the lower court's decision, agreeing she had cause. It was reopened in late 1878 in Vanderburgh Circuit Court. Nothing was decided until March 1880, when she proposed a compromise to the Board of Commissioners. She'd settle if the county agreed to pay $200 ($6,000 in today’s dollars) for damages and the cost of the suit. They agreed, and the case was dismissed.

In late 1878, the Commissioners received a petition to remove the poor farm and pest house from the Columbia Street area. Around 1882, it was moved out of town to the end of Stringtown Road.

Luckily, she lived long enough to see her prayer answered - the pest house moved. She died in 1895 at the age of 78. What a bold, brave, and strong woman who stood up and fought for her children and her community and won. I’m proud to have her as part of my lineage.

An amazing woman and a great read!

Catharina was am amazing woman! How heart-wrenching it must have been for her losses. I can understand what an uphill battle she faced in that time and place in her quest for recompense. Brava to her!