Becoming Betty

Bessie Simpson/Betty Devereaux (1892-1958)

In February 1913, trans-Pacific steamships docked regularly in San Francisco Bay, bringing goods and passengers from Asia to a city still rebuilding from the devastating 1906 earthquake. The British steamship Persia, operated by the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, made regular runs between San Francisco and Asian ports including Honolulu, Manila, Shanghai, and Yokohama, and carried both commercial cargo and human ambition.

On February 25, 1913, when the Persia glided through the Golden Gate, among its passengers was a 20-year-old single woman returning from six months touring Asia with a theatrical company. She gave her name as Betty Devereaux.

But Betty Devereaux had not always been Betty. To understand how she arrived in San Francisco with a new name and a new life, we must return to an earlier time and place: Evansville, Indiana.

Evansville at the Turn of the Century

In 1900, Evansville was an industrial river city of about 60,000 people. Its economy was powered by factories, mills, and trade along the Ohio River. Working-class families lived in densely packed neighborhoods where wooden houses stood close together. Men worked in the factories and mills, and women and their daughters often helped support the household by taking jobs at the Evansville Cotton Manufacturing Company.

In 1900, eight-year-old Bessie Simpson lived with her parents, William Henry Simpson and Dorothy (Dolly) Simpson, and her aunt and uncle in one of these Evansville neighborhoods. The Simpson family would have been surrounded by other working families, by the sounds of industry, by the rhythms of a life where survival required long hours and steady work. Childhood in such neighborhoods meant playing in the streets with other children, attending local schools and churches, and families staying together even when that meant enduring unhappiness or worse.

William Henry Simpson worked as a sawyer, trimming and cutting lumber for one of the 41 furniture factories in Evansville. But by 1900, he had been battling pulmonary tuberculosis for what would become a two-year struggle with the disease. Tuberculosis, then called consumption, was one of the leading causes of death in early twentieth-century America, particularly among working-class people living in crowded urban conditions. The disease was wasting, terrifying, and often fatal. There was no cure. Patients grew progressively weaker, coughing and struggling to breathe, watching themselves deteriorate over months or years.

Whether William’s illness contributed to the breakdown of his marriage is unknown, but by June 1902, Dolly Simpson had done what many women in her position could not; she had left her husband. She moved to a west-side boarding, hired Attorney R. C. Wilkinson, and filed for divorce. In an era when divorce carried social stigma and when many women lacked the economic means to survive independently, Dolly’s actions represented both courage and desperation.

On the evening of June 19, 1902, William Simpson came to Dolly’s boarding house and made his position clear: “If she did not return to him, she would not live at all and that he would not live either. He told her he would do what he meant to do before the sun went down.” He had made such threats before Dolly told the court. Once, he had brandished a revolver and warned that if she didn’t shut up and behave herself, there would be another “Conway” affair, referring to a recent bloody triple tragedy on the West Side that would have been fresh in every Evansville resident’s mind.

The next morning, Dolly filed a sworn statement asking the court for a peace bond for her protection. The Evansville Journal reported the story that afternoon, describing a thirty-year-old woman terrified by her husband’s threats, working at the cotton mill to support herself, with a little daughter, ten-year-old Bessie. After a hearing, Justice Francke ordered William to post bond to keep the peace. When he failed to do so, he was sent to jail. Three months later, on September 27, 1902, William Henry Simpson died at age thirty-five. The cause of death was pulmonary tuberculosis, the disease that had been consuming him for two years. He died in Evansville, still married to Dolly; the divorce she had filed was not yet final.

Looking back, William’s threats take on a different light. He was a dying man, watching his wife slip away as his own strength faded, and he may have understood the end was close. Whether that made him more dangerous or simply more desperate, we don’t know. What we know is that Dolly took them seriously enough to go to court, and that ten-year-old Bessie lived through all of it: the threats, the court hearing, her father in jail, his death three months later.

We don’t know whether Bessie visited her father before he died, whether she was present at the end, or whether she grieved or felt relief. Those details are lost. What we know is that she was old enough to understand what had happened.

Going West: Denver and the Missing Years

According to an article in the Evansville Journal dated July 8, 1904, Bessie and her mom were already living in Denver. In 1905, when Dolly married Jacob Kraft, the city was booming, with a population of more than 200,000 people. Jacob, originally from Rochester, New York, gave Dolly a new name and Bessie a stepfather.

From 1905 to 1912, the historical record offers almost no trace of Bessie’s life. However, I found another thread that points back to Denver: the Evansville newspaper noted that Dolly’s sister-in-law, Maggie Simpson, was visiting there in 1908 and 1909. It doesn’t prove where Dolly and Bessie were living, but it suggests they still had ties to the city during that period. Between ages twelve and twenty, she would have attended school, perhaps worked, and almost certainly began shaping the ambitions that later propelled her toward the stage. Whether she stayed in Denver, moved to Rochester where Jacob came from, or lived elsewhere, we cannot say. But we know that by August 1912, Bessie Simpson had joined the Ferris Hartman Musical Comedy Company, preparing for a six-month tour of Asia.

For a young, unmarried woman to join a theatrical troupe in 1912 was to risk stepping outside conventional respectability. The early twentieth century did bring women more opportunities. The suffrage movement was gaining momentum, and women were entering colleges and professions in growing numbers. But becoming a chorus girl still carried a whiff of scandal. Theatrical women were often viewed as modern and daring, yet also morally suspect. They traveled without chaperones, performed for strangers, and lived in ways that challenged the domestic ideal dominant in American culture. Bessie’s decision to join the troupe suggests not only talent and ambition, but a willingness to embrace uncertainty. She left behind whatever life she had known for the promise of the stage.

Six Months Across the Pacific

In August 1912, the Ferris Hartman Musical Comedy Company departed San Francisco aboard the Persia. American theatrical companies regularly took vaudeville, musical comedy, and light opera overseas, performing for expatriate communities and for local audiences curious about American culture. These tours could be genuine cultural exchanges, but they were also practical business. There was money to be made entertaining Americans stationed abroad and affluent audiences eager for modern Western entertainment.

Life aboard the Persia was a mix of hard work and enforced downtime. The chorus girls rehearsed daily to keep their numbers sharp for each port. They lived in cramped shared cabins, wedging costumes and trunks wherever they could. When the sea turned rough, seasickness was common, but rehearsals still went on. In the hours between practice and performance, they mended costumes, tended sore muscles and minor injuries, and tried to rest. The ship was both transportation and temporary home, and the troupe became its own close-knit world, held together by shared purpose and shared discomfort.

In Honolulu, the company played for three weeks, long enough to be serenaded by bands and royalty. The chorus girls learned the hula from Hawaiian dancers and tried to teach them to “rag” though the Oakland Tribune later reported that the Hawaiian women could not get the hula entirely out of their movements no matter how much rag they added. The cultural exchange was real, even as it showed its limits.

Manila, a U.S. colonial possession since the Spanish-American War of 1898, offered a different experience. The troupe performed for six weeks to American audiences, including soldiers, administrators, and businessmen stationed in the Philippines.

In Japan, the troupe discovered that expressions of pleasure could cross cultural boundaries in unexpected ways. Company manager Ferris Hartman later explained that Japanese audiences would show their teeth and draw in their breath with a sharp intake of air, a sound that at first made American performers think they were being hissed at rather than applauded. That moment captured the strangeness of performing across cultures, and the way even laughter sometimes needs translation.

In Shanghai, often called the “Paris of the East,” the American girls found themselves showered with gifts. When they returned to San Francisco months later, some wore rich furs from the Siberian coast, along with rare laces and mother-of-pearl ornaments given by admirers. The Tribune reported that “the American girl is always queen in Shanghai” reflecting real fascination with modern American women.

Somewhere during these six months—aboard ship, in a foreign port, in the close quarters of the traveling troupe—Bessie Simpson became Betty Devereaux. The name change was more than cosmetic. It represented a shedding of the past, a conscious reinvention. Betty Devereaux was who she would be when she set foot on San Francisco soil in February 1913.

San Francisco: Art, Ambition, and Reinvention

When Betty returned, San Francisco was a city in transition. Nearly seven years after the 1906 earthquake and fire had destroyed much of the city, San Francisco was rebuilding not only its streets and buildings, but also its cultural identity. The planned 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition was meant to be proof of that recovery, a grand welcome that would put the rebuilt city on display.

It was also a city where the arts scene, and the bohemian circles around it, could make room for women willing to step beyond conventional boundaries. San Francisco’s art community included artists, sculptors, painters, theater people, and patrons who mixed at balls, galas, and charitable events. For a young woman with theatrical experience and social ambition, San Francisco offered possibilities that Evansville never could.

When Betty made a brief visit to Evansville in August 1913, the local newspaper reported that Miss Bessie Simpson, a former Evansville girl, was visiting before leaving for New York, where she would make her home. However, for unknown reasons, Betty did not go to New York. She returned to San Francisco to build her new life.

By 1915, Betty had become part of San Francisco’s art world enough that she was asked to model for a statue at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. The exposition drew millions of visitors, celebrating both the completion of the Panama Canal and San Francisco’s resurrection from earthquake and fire. However, while the Evansville paper reported that her statue was in the Court of Palms, I could not find any documentation to confirm that fact, or any specific figure in that court. For her to be named as a model at all suggests both recognition and a particular kind of visibility. She fit an ideal of modern American womanhood that the fair loved to display: young, graceful, and fashionable.

The exposition also brought together artists and patrons from across the country. Among those who exhibited was Edgar Walter, a sculptor who had studied at San Francisco’s Mark Hopkins Institute and in Paris, and whose work included an elaborate Beauty and the Beast fountain for the Court of Flowers. Whether Betty and Edgar met at the exposition or in the broader social world of San Francisco’s arts scene is unknown, but by 1915, their paths were beginning to intersect.

By October 1916, Betty appeared in the San Francisco Examiner society pages including being photographed at a Cubist-Futurist ball at the St. Francis Hotel. The Cubist-Futurist ball reflected San Francisco’s engagement with the modern art movements sweeping through American culture in the 1910s. By attending events like this, Betty aligned herself with the city’s modern set and signaled that she belonged there. Edgar Walter was known not only for his sculptures but for supervising decorations at these sorts of charitable balls and galas.

By February 1919, when Betty’s mother Dolly (now widowed from Jacob Kraft and living with Betty) hosted a supper dance for 150 guests, Edgar Walter was on the guest list. The social world of San Francisco’s arts community was small enough that artists, patrons, and performers knew each other, attended the same events, and moved in the same circles.

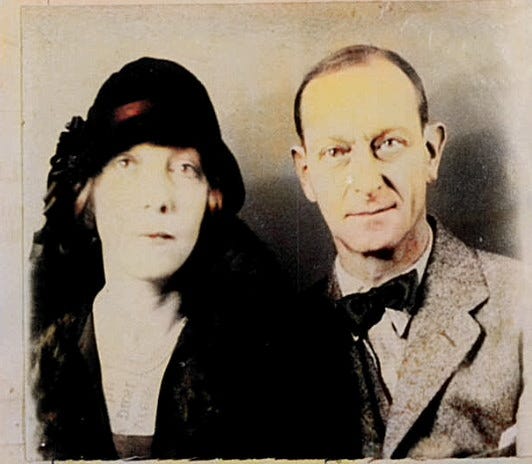

On July 3, 1920, Edgar Walter and Betty Devereaux quietly married in Redwood City. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that the event came as a surprise to many of their acquaintances. Betty was described as well-known in San Francisco society and art circles, and as a friend of Princess Troubetzkoy. There was no mention of Evansville, no mention of Bessie Simpson, no mention of the threats made eighteen years earlier in a west side boarding house.

Betty Devereaux had successfully reinvented herself. She had transformed from a child marked by domestic violence into a woman who moved comfortably in San Francisco’s cultural elite. The transformation was not accidental; it required deliberate choices, sustained effort, and the willingness to leave the past behind.

Epilogue: A Legacy of Beauty

Betty Devereaux and Edgar Walter remained active in San Francisco’s art world through the 1920s and 1930s. Edgar continued his own work, served as director of the San Francisco Art Association, and became president of the San Francisco Art Commission. He also collected rare etchings by Rembrandt and Albrecht Dürer, among others. Over time, Betty developed her own expertise as a connoisseur, earning respect from dealers and collectors. Edgar died on March 2, 1938. In his will, he left $150 per month (over $3,400 in today’s money) to Betty’s mother, Dolly Simpson, for the rest of her life.

Betty later remarried and divorced, but when she died on October 22, 1958, at age sixty-six, like other women of that era, her obit lists her as the “widow of San Francisco sculptor Edgar Walter.” In her will, she left an art collection valued at approximately $300,000 (over $3.5 million in today’s money) to the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, a legacy that testified to a life built on her love of art rather than defined by violence.

Betty never used the name Simpson again. The erasure was complete and deliberate, and in its own way, triumphant. She had escaped. She had rebuilt. She did not just change her name. She became someone new.

Sources

California, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1959, British Steamer Persia, arrived in San Francisco 25 Feb 1913, passenger Betty Devereaux; NARA microfilm publication M1412, San Francisco 1903-1918, roll 08.

Stats Indiana, “Indiana City/Town Census Counts” https://www.stats.indiana.edu/population/poptotals/historic_counts_cities.asp, accessed 8 Feb 2026).

IHB Marker Review 82.1996.1 Evansville Cotton Mill, Vanderburgh County, 9 Sep 2013, 3; digital image, Indiana Historical Bureau (https://www.in.gov/history/files/82.1996.1review.pdf : accessed 8 Feb 2026).

1900 U.S. Census Enumeration district 94, Dwelling/family numbers 53-55, 14. Bessie Simpson listed as daughter, single, residing with parents in Evansville, Vanderburgh Co., IN.

Robert Patry, City of Four Freedoms (Evansville: Friends of Willard Library, 1996), 35.

Death certificate for William H. Simpson, 27 Sep 1902, Vanderburgh Co., IN; Indiana State Board of Health, Certificate of Death, Record Number 703; Indiana, U.S., Death Certificates, 1899-2017; digital image, Ancestry.com.

Susan L. Speaker, “Collecting Data about Tuberculosis, ca. 1900” Circulating Now: From the Historical Collections of the National Library of Medicine, 31 Jan 2018, National Library of Medicine (https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2018/01/31/collecting-data-about-tuberculosis-ca-1900/ : accessed 2 Feb 2026).

“Defendant Goes to Jail in Default of Giving Bond,” Evansville Journal, Evansville, IN, 20 Jun 1902, 9; digital image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com : accessed 8 Feb 2026).

“Bessie Simpson visits friends,” Evansville Journal, Evansville, IN, 8 Jul 1904, 10; digital image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com : accessed 8 Feb 2026).

Marriage record, Dorothy [Simpson] to Jacob Kraft, 1905, Denver, CO. Colorado, US, County Marriage Records and State Index, 1862-2006. No. 35892, digital image, Ancestry.

“Comic Opera Was Welcomed in East: California Dancing Girls Taught Honolulu Hula-Hula Girls to Rag,” Oakland Tribune, Oakland, CA, 16 Mar 1913, 23; digital image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com : accessed 8 Feb 2026).

California, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1959, British Steamer Persia, Pacific Mail Steamship Company, arrived in San Francisco 25 Feb 1913; NARA microfilm publication M1412, San Francisco 1903-1918, roll 08.

National Park Service, “The Panama-Pacific International Exhibition,” https://www.nps.gov/goga/learn/historyculture/ppie.htm, accessed 8 Feb 2026.)

San Francisco Women Artists, “Past and Present” https://www.sfwomenartists.org/about-us/, accessed 8 Feb 2026.

“News of the West Side,” Evansville Courier and Press, Evansville, IN, 27 Aug 1913, 4; digital image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com : accessed 8 Feb 2026).

“Statue Model an Evansville Girl,” Evansville Press, Evansville, IN, 7 Aug 1915, 10; digital image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com : accessed 8 Feb 2026).

“Sculptor Walter and Miss Devereux Wed,” San Francisco Chronicle, San Francisco, CA, 4 Jul 1920, 9; digital image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com : accessed 8 Feb 2026).

“Futurist Ball Event of To-Night,” San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco, CA, 17 Oct 1916, 11; digital image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com : accessed 8 Feb 2026).

“Group of Friends gathered to enjoy supper dance for Central Americans,” San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco, CA, 16 Feb 1919; digital image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com : accessed 8 Feb 2026).

“Death of Edgar Walter,” San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco, CA, 3 Mar 1938, 15; digital image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com : accessed 8 Feb 2026).

“Mrs. Sirigo Dies in Menlo Park,” San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco, CA, 24 Oct 1958, 55; digital image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com : accessed 8 Feb 2026).

“Death of Dorothy Montgomery Kraft,” San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco, CA, 13 Jun 1960, 57; digital image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com : accessed 8 Feb 2026).

Loved this story, Lynda! So interesting and well written.

What a fantastic story, Lynda! I need to check out the https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palace_of_Fine_Arts to see where her sculpture might be. It’s a beautiful area today though largely rebuilt.